Day 56 – Unsettled, but calmer with a litte history

Day 56 – Still trying to root out my unsettled feelings about Western

philosophy – I tried to take a bit of a deep dive today in philosophy. I was looking specifically for feminist

critiques of the philosophical canon – (mind you, this is not a statement I

would have said a while back!) I allowed myself to wander around the web. Reading

bits of books and papers. One thing that stood out was the idea that “who” was

defining “truth” made a difference, that what was considered a “way of knowing”

was important, and that often the ideas of what was being looked at was also

important. One way into these schools of

thought was literary criticism.

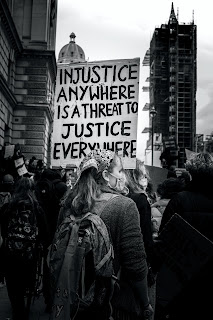

Photo by Hans Eiskonen on Unsplash

In their page about “Writing in literature” the Purdue online writing lab describes “Literary theory and schools of criticism” this way:

A very basic way of thinking about literary theory is that these ideas act as different lenses critics use to view and talk about art, literature, and even culture. These different lenses allow critics to consider works of art based on certain assumptions within that school of theory. The different lenses also allow critics to focus on particular aspects of a work they consider important.

They then go on to give a brief overview to multiple critical theories.

Timeline (most of these overlap)

· Moral Criticism, Dramatic Construction (~360 BC-present)

· Formalism, New Criticism, Neo-Aristotelian Criticism (1930s-present)

· Psychoanalytic Criticism, Jungian Criticism(1930s-present)

· Marxist Criticism (1930s-present)

· Reader-Response Criticism (1960s-present)

· Structuralism/Semiotics (1920s-present)

· Post-Structuralism/Deconstruction (1966-present)

· New Historicism/Cultural Studies (1980s-present)

· Post-Colonial Criticism (1990s-present)

· Feminist Criticism (1960s-present)

· Gender/Queer Studies (1970s-present)

· Critical Race Theory (1970s-present)

· Critical Disability Studies (1990s-present)

Wow – I was slightly overwhelmed by the depth of theoretical approaches here. But I also feel as though I am starting to understand a bit more about the larger context of these area of study. I was particularly curious about a reference to Alice Walker’s work, In search of our mothers’ gardens: Womanist prose.

All of this interest in philosophy sent me back to a paper I wrote in the spring of 1998 while studying for a doctorate in Clinical Psychology. The course was a history of psychology class, and we were directed both to write small essays twice a month, and to do a final paper.

My final paper was on postmodernism, but before that paper was written, I wrote a brief paper on the history of philosophy – because I needed to familiarize myself with the information. I’m including that below… (I should note that I couldn’t find my reference list for this paper, but I believe they will be in the paper I post tomorrow on postmodernism. Enjoy!

A BRIEF HISTORY OF “MODERN” PHILOSOPHY

The modernist movement, like postmodernism, is multidimensional. The term “modern” is not used to mean contemporary, but rather to refer to a specific intellectual discussion “developed in Europe and North America over the last several centuries and fully evident by the early twentieth century” (Cachoone, 1996, p.11). What made the modern movement unique was the development of the scientific method. The development of machines, technology, and industrialization all resulted from scientific advances, and these led to a level of material living standards that had hardly been imagined. In addition, other traits which came to be associated with modernism were “capitalism, a largely secular culture, liberal democracy, individualism, rationalism, (and) humanism” (p.11). One factor that contributed to psychology’s affiliation with the “cult of empiricism” (Toulmin, 1992) was the fact that as a discipline, psychology came of age during the height of the modernist project.

Depending on which basic tenet of modernism you emphasize, you have a different starting point for modernism. Some people believe that modernism begins with the Protestant reformation - by rejecting the universal power of the church and relying instead on humanistic skepticism one moves from the idea of an all-unifying God, to a “secular dream of a physical universe made completely translucent by this same universal reason” (Jager, 1991, p.61). In other words, a pre-modern faith in God, became a modern faith in science. Most people feel the modernist movement began with Descartes and the scientific revolution - the belief in a universal capacity to “reason.” This capacity to reason brings with it a method which implies individualized freedom and the promise of progress. Because reason is no longer dependent upon authority (the Divine right of Kings) or tradition (the Divine knowledge of the church), man can objectively and systematically encounter truth, beauty, moral goodness, and political order, on his own, as an individual, and thus find the meaning of human existence. “The legacy of the Enlightenment, (is) the simple, profound unquestioned conviction that Reason, Freedom, and Progress naturally imply one another” (Cachoone, 1996, p. 27). Others feel the modernist movement began with the political revolutions of eighteenth-century France and the US, and still others argue that the modernist movement has its roots in the nineteenth century industrial revolution (Cachoone, 1996).

The questions of “what we can know” and “how” have been answered in a variety of ways over the years. The various philosophers and schools of philosophy have approached these questions with different emphases. At times discovering “truth” through reason was emphasized, at times reason was subsumed by inquiry through sensory experience. At times, thinking was the primary vehicle for discovery, at other times it was imagination. At times discovery was emphasized, at other times methodical uncovering was emphasized with a belief that the ultimate truth can never be known but only approximated. Yet all these twists and turns of a modernist approach to knowledge found their roots in a “logic of justification” which has come to be accepted as the scientific method (Loving, 1997). This logic of justification can be said to have begun with Frances Bacon in the early 1600’s and involved “two notions of induction - one depending on pure discovery, the other a more practical step-by-step method involving observing then testing guesses (hypotheses) along the way” (Loving, p.428).

Bacon’s contributions within the “Age of Reason” were followed by Descartes’ contributions and the period known as the “Enlightenment.” Descartes’ famous dictum, “I think, therefore I am,” solidified man’s essence as rational. Descartes was responsible for initiating a shift in the traditional philosophical discourse of the time from a “preoccupation with wisdom to a preoccupation with acquiring ‘knowledge.’ The new idea was that first we must talk about what is certain, and only then will we have sufficient grounds for talking about what is real and how we should live” (Linn, 1996, p.2). Descartes introduced several concepts within his philosophy that have remained, for philosophy, fundamental problems. The problems of representationalism, body/mind split, fundamental detachment, passions vs reason, and subjective vs objective knowing, all find their roots in “Cartesian” (Descartes’) philosophy. Descartes advocated for man to rely on his reason alone, not on feeling, nor on faith. By relying on reason, Descartes believed that we were essentially detached from our surroundings, free to choose what to believe and how to act. Through our reason we could “search for representations of the world which are absolutely certain” (p.4), and thus we could “defeat the unruly passions that lead to error and an immoral life” and “discover the truth about the rational universe” which surrounds us (Linn, 1996). The notions of “certain representations” and “essential detachment” become fundamental errors according to the postmodernists.

One of the earliest critics of the Enlightenment was Rousseau. Rousseau is thought to be the father of Romanticism. The Romantics believed we should return to the “tacit state of experience prior to intellectualization... (with an) emphasis on interrelated wholeness of experience, access to such wholeness by means of tacit processes - affect, intuition, kinesthesia, and imagination, and qualitative or descriptive accounts of such processes” (Schneider, 1998, p. 278). Hume, another critic of the Enlightenment, felt that “without feeling or passion there would be no moral behavior,” and that “reason alone leads nowhere” (Linn, 1996, p.14). For Hume, human life is given a determinate shape by an essential species nature, reason must be the slave of passion - only with active imagination, will we survive. Rather than an innate reason, it must be an innate feeling that is the root of life. “Our ideas must be either innate or produced by direct bodily experience” (Linn, p.15). The romantics, influenced by Hume and Rousseau’s emphasis on feeling, felt that the highest and most needed truths are subjective rather than objective - intuition and feeling rather than reason led to truth and that through feeling man’s essential nature as good and redemptive can be accessed. The Romantics were ironically aided in their critique of the Enlightenment by Kant, who was described by one author as “the high priest of reason” (Linn, p.6). For although Kant emphasized a rational human structure, his mind was active and known subjectively.

Kant proposed that “we cannot know anything about what the world is like ‘in itself’ independent of its appearance in the mind” (Linn, 1996, p.8). This led to a belief in a priori judgements. For Kant, objectivity is subjective in origin and therefore phenomenal. Kant begins with sense experience, which is mediated by the imagination and then actively, organized through the mind. Yet this involvement of the imagination and senses is not to be confused with a denial of reason on Kant’s part. He believed that feelings and the imagination were irrelevant to moral decisions. Instead, he advocated that we rely on our true essential rational nature which he felt would emerge from innate mental categories and lead to universal principles and rules. For Kant “all human minds think in terms of the same basic innate categories,” thus although one cannot know all of the world, one’s experiences could be mediated through the imagination and then coherently, actively, organized according to one’s innate, universal, rational human structure (Linn, 1996, p.9). Despite his clearly Enlightened message, Kant is also often cited as offering a preview of the postmodern idea that knowledge is not implicit, nor passively registered, but rather constructed.

Yet the notion of a constructed reality was not yet a notion which could be tolerated. In fact, even Kant’s notion that some judgements relied on a priori knowledge was questioned by the empiricists. Although a continuation of the modernist project, empiricism concentrated less on “what” the mind knows, than on “how” it knows. The empiricists believed that it was only through experience (ie: carefully documented observation) that truth could be found. This experience could be sensory but could also be reflective. Thus, for the empiricists, “although all ideas were derived from experience, they were not all derived from direct sensory experience; some were the products of the mind from the processes of reflection” (Benjamin, 1988, p.58). This pure empiricism, articulated by John Stuart Mill, held that ultimate laws of nature that were deterministic could be empirically validated. Empiricists began to disbelieve “any a priori element of a formal character in a theory” (Loving, 1997, p.438), and instead began to reduce statements about theory into statements about sensation, to reduce theory to phenomenal (observable) language.

Thus began another split within the modernist movement - the split between that which was observable and that which required theoretical terms, and which relied on metaphysics. The logical positivists, a group of mathematicians, logicians, and physicists, known as the Vienna Circle, came on board with the notion that science is composed of truth found in statements which correspond to factual observations (Benjafield, 1996, p. 195). These theorists proposed that the only legitimate knowledge was knowledge based on “mathematically expressed and deductively joined statements of lawful relationships among observables” (Steenbarger, 1993, p.57). What the logical positivists hoped to do was to allow for a method which could diminish the effects of subjectivism on knowledge acquisition, and to do away with the “failure to employ a perfectly clear, logical, ‘ideal language,’ which the new advances in logic... had made possible” (Cahoone, 1996, p.6). They hoped to finally develop a “systematization of human knowledge ...based in the certainties of modern logic combined with a scientific explanation of ‘sense data’” (Cahoone, p.6). But this method brought into question our ability to define “truth” separate from theory. Were we to define our direct, unmediated by theory, awareness of some things? Or could these observations allow us to construct theories based on what we observe directly - that is, give us indirect, theory-mediated, knowledge of an independent reality? In either case, the modernist view held that there was an independent reality to know - “what” we know of it and “how” we know it continues to be hotly debated.

PSYCHOLOGY’S MODERNIST MISSION

The modernists believed in an essential nature which gives shape to the way we think and live in the world. The rationalists believed that general laws and truths may be attained by way of reason. The romantics also believed in an essential nature, but they rejected the emphasis on causal linear knowledge (Schnieder, 1998, p.278), instead they emphasized finding truth through feeling. The empiricists focused on the method by which we know. And the philosophy of science was becoming all pervasive within Western philosophy. As we moved into the twentieth century, specialized fields of study were established each with their own “logic of justification.” From the empiricists, a set of procedural rules were established. These rules, which defined the “scientific method,” were adopted by various disciplines, including psychology. The logical empiricist philosophers “saw the possibility of unifying all scientific endeavors under a single logic” (Gergen, 1992, p.18). This unity, while providing a common language for scientific inquiry, paradoxically allowed the field of psychology to feel it could clearly distinguish itself from philosophy and other disciplines. By aligning itself with the natural sciences, psychology hoped to legitimize itself as an autonomous discipline, and to discover, unfold, describe, and define the “truth” about the human mind and human behavior.

Comments