Day 35 – Social capital

Curiosity, a capacity or desire for complexity, time to reflect, resources for tackling these complexities – these are often accessible when you’re not struggling to survive. When you are – your intellectual resources are often being used in the struggle for survival. As a result, I try to “stay local” – understand my little corner of the world and not try to over-reach my grasp of things. I think this also has to do with feeling as a young person that I had little social capital – I had moved around a lot as a young child (my father was a career Army man). I didn’t grow up with family knowledge – embedded in the history of a community or in a community where my family was a known group. There weren’t books or art or even newspapers in my house growing up after my parents separated when I was 12. My dad was a reader, but my mother was not. My grandparents had no “narrative” to offer me about their childhoods or what it meant to grow up on the “island.”

I entered high school at a very troubled time in my life. I was not tracked as a potential college student – even though I went to a college prep exam high school (I never took calculus, or physics, or an AP history or English course, or even a world history course). As a first-generation college student, I didn’t really know what I needed to know or not know when I went to college.

When I went to college, I got a bachelor’s in music and studied music therapy. This meant I also had few courses outside of the conservatory – and this left my general fund of knowledge quite limited. I had never taken a philosophy class, a political science class, an American studies or history class.

I also wasn’t prepared for my conservatory classes – I think most of my classmates had studied piano as children even if they played other instruments (I was a flautist). This piano playing gave them a rudimentary sense of music theory – chords, harmony, multiple voices, which I did not have when I began “studying music.” Thinking back on it, I am amazed that I even survived those years. I worked hard!!

As I read the texts I am describing on this blog, I’m a bit in awe of the differences in my fund of knowledge now, and in my fund of knowledge as a 23-year-old entering into the Graduate Program in Expressive Therapies in 1982. Part of that is just growing older, but a lot of it is just trying to make up for lost years of not being exposed to what I see most “middle-class” folks learning in high school. I try to keep this in mind as I teach.

I’m reminded of my doctoral dissertation. I wrote my dissertation on class-consciousness in first-generation doctoral level psychologists who practiced psychotherapy. I wanted to understand “the impact of social class mobility on the personal and professional identities of doctoral-level psychotherapists from working-class backgrounds” (from my dissertation abstract).

I used a qualitative research methodology called The listening guide. I’m including a section of the conclusion here – because it seems relevant! At least it’s been good to revisit as I try to do something so solidly “professional,” and as I recognize this writing as “work.”

Each of the three major themes emerged out of multiple listenings of each interview. First, social class identity is multiply determined. Social class as a marker of identity can be fully understood only in relation to other cultural identities (e.g. race, gender, sexual orientation, regionality) and within a larger historical and sociocultural context. An individual’s social class identification and class consciousness are also products of multigenerational negotiations of class identity. For the participants in this study, factory work, semi-professional work, and issues of immigration all played a role in these multigenerational negotiations.

In describing their journey of upward mobility and in locating themselves in relation to the professional class as psychologists, interviewees spoke eloquently of their parents’ and grandparents’ work lives and educational backgrounds and the influence these experiences had on their career choices and path. In addition, while other studies related to first generation college students note the impact of parents’ support and familial reactions to class mobility during college (Ochberg & Comeau, 2001; Roberts & Rosenwald, 2001), it is clear that issues of identity and reverberations of class mobility do not end there. Class identity impacted the clinicians in this study well into their careers.

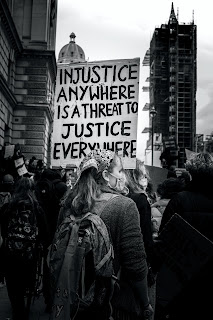

Second, educational advancement and the steps of professionalization, such as internship, clinical training, and early career practice, allowed each participant to travel along the path of upward mobility from the working class to the professional class on their way towards becoming psychologist psychotherapists. The journey to becoming a professional for those from the working-class is, however, fraught with contradictions and conflicts of loyalty. Within the larger culture these accomplishments and challenges are often framed as personal achievements or failures of an individual with little acknowledgement of larger societal, structural or systemic dynamics influencing opportunities or obstacles for social transformation. Awareness of these dynamics in the form of class-consciousness was evident for some participants and remained elusive for others. This awareness allowed some to mitigate the identity negotiations within themselves and with their families and the larger community. However, for others this transition remained hidden within a larger narrative of personal change via upward mobility.

One impact of class mobility on professional identity for these psychotherapists lay in their reconceptualizations of work. Where work had previously been defined as highly regulated labor dictated by the government or a large company, or manual labor, or work that required long hours, harsh conditions, and visible results, work was now defined by these psychotherapists as a “practice” rooted in relationship-building and in the application of psychological principles and skills. For these participants, the practice of psychology – and psychotherapy in particular – required a reconceptualization of work to include a profession that often allowed for more control, respect, and autonomy than any of the jobs held by previous generations of their family. This process of upward mobility and reconceptualization of work led some participants to negotiate a hybrid of working- and middle-class identities, while leading others to establish a bicultural identity or a solidly middle-class identity, and still others to reject a middle-class identity altogether.

Third, the impact of class identity on clinical practice – specifically as related to subtle negotiations of power and to the negotiation of class-based transference and countertransference reactions – emerged as participants examined the effects of class mobility on their practice. These clinicians reported having to tolerate powerful feelings of envy, shame, inauthenticity, arrogance, pride, and confusion as they navigated the experience of being seen as powerful and privileged or in fact being more powerful and privileged in relation to their clients, students, employees, families, or colleagues. These therapists described their experiences of modulating a sense of dislocation when being referred to as “Doctor,” or their care in not judging clients with fewer resources, or their sense of wonder at overt classism on the part of colleagues. These attentions to relational dynamics were augmented by logistical concerns. Debt and struggles to legitimize professional status through the setting of fees also emerged as an example of identity negotiations related to class. Despite the challenges of these negotiations on identity and practice, one potential benefit of class mobility for these therapists appeared to be a greater appreciation for the multiple identities held by clients, students, and employees, and an increased sensitivity to issues related to class within the practice of psychotherapy.

Estrella, K. (2009). Class in context: A narrative

inquiry into the impact of social class mobility and identity on class

consciousness in the practice of psychotherapy (order No. 3376895).

Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. (305172682).

Comments