Day 10 - Decolonizing expressive arts therapy training, theory, research, and practice – pt. 2

|

| Photo by Aaron Burden on Unsplash |

While forward-thinking in his recognition of the foundations of arts-based “healing” practices within indigenous cultures, McNiff’s linking modern arts therapy and shamanism (see also McNiff, 2004) has come to be seen as failing to acknowledge, critique, or guard against the possibility of cultural appropriation or misappropriation of traditional practices. McNiff (2004) is clear that he is not speaking “literally about creative arts therapists as shamans,” nor has he “presented” himself as a shaman; rather he is aligning the work with “the more primal, sacred, and universal process of indigenous healing” (p. 181-182).

Storytelling, myth, ritual, dance, song, and encounters with the body/mind/soul lie at the heart of many indigenous methods of healing in community (Archibald & Dewar, 2010). Expressive arts therapists revel in the idea that our practice is ancient, “universal,” and multimodal. We justify our multimedia approach by stating that some cultures have the same word for dance and music (e.g., the Suya Amazonian people have one word for music and dance – “ngere” according to Campbell & Seeger, 1995, p. 20; see also Lewis, 2013).

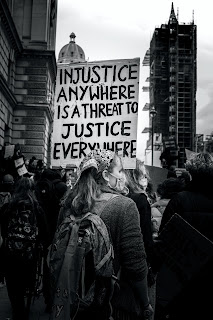

Yet few expressive arts therapists themselves belong to indigenous communities. And fewer are practicing in communities which can embrace indigenous methods without risk of appropriation. The question of “whose” art we are using and “whose” methods we are using is one which needs further critical examination (Estrella, 2017*).

As I look back on those words two years later, I see that I do not challenge the harm of universalism enough! And that I have not recognized the long arm of the history of this careless appropriation. I also struggled then, and continue to struggle now, with how and whether to acknowledge the use of multi-arts approaches to healing in indigenous communities, without aligning expressive arts therapy with those approaches. I believe to do so carries too strong a temptation to exotify, decontextualize, and appropriate those approaches. What is the motivation for expressive arts therapists in aligning ourselves with indigenous healing practices? And where does that practice lead us?

Certainly, one problem with this alignment is the notion that our practices are “ancient” (another variation on “universal”) or that simply because indigenous communities use a multi-arts approach to healing, this gives us some claim to “authenticity.” There is also a danger of thinking of our work as containing “ritual” without rooting that ritual in an appropriate context. If we are to decolonize our work, I believe we must acknowledge the ways we have erased, co-opted, and exotified community practices of the arts.

For many years, pre-COVID, the orientation for our program took place in a camp setting away from the city where we are located. I always thought of these sessions as an invitation to orient our students to the program in a “retreat” setting. (Orientation took place in the foothills of the White mountains of NH by a pond where one could boat and swim.) Unfortunately, because the orientation took place in August, and because the site was in fact a “camp” with bunk houses, a camp dining hall, and camp staff, many of our students (and faculty) associated this experience with summer camp – and later referred to it as “camp Lesley.” This “colloquium” had been taking place since the program began in the mid-1970s, and many generations of graduates had many a tale to tell of their Orientation experience, but somehow by 2020 our students’ response to “camp” had shifted significantly.

Over the many years I attended Orientation as an instructor, I saw the experience as an opportunity to enter a “liminal” space and to mark the beginning of one’s studies in the arts therapy with one’s whole self. I believed Orientation invited our students to reclaim a childlike willingness to play and enter a creative space, in what I saw as a multi-arts studio retreat. I believed in the importance of beginning the program away from the everyday worries of securing housing, getting work, moving, etc. and saw the “natural” setting as giving us an important opportunity to incorporate nature into our beginning.

Unfortunately, I did not question the long, extremely problematic relationship between summer camp and “camp traditions which imitate, appropriate, and misrepresent Indigenous ceremonies, names, and cultural practices of dress and craft” (Shore, 2015). While many of our communal activities such as storytelling, drumming, and dancing around the campfire in the evening were not framed within an “indigenous” context, neither were they contextualized, and there was in the end a blurring of the lines between our experience of these activities as “appropriate” for orienting our students to the art of being “free” in their expressive-ness.

It feels like there is so much to unpack here, and I’m not quite sure how to do so. “Camp Lesley” became problematic for many reasons, and certainly too many for me to fully unpack here. I also have beautiful memories of community and community sharing that took place at Orientation over the years. But as an example of the need to revisit expressive arts therapy training, theory, research, and practice from a lens of critical pedagogy and decolonization, camp provides a huge cautionary tale. I want to acknowledge my own complicity in approaching this experience without enough of a critical lens. I hope that as I continue to work to articulate my view of the field from this perspective a more just approach can be found.

Shore, Amanda. (2015). Notes on Camp: A Decolonizing Strategy Retrieved from https://ccamping.org/research/camp-research-papers/

* If needed, please email me directly at estrella@lesley.edu for complete citations.

Comments