Day 67 and Day 68 – Neoliberalism, subjectivity, and person-centered psychotherapy, part 2

|

| Photo by engin akyurt on Unsplash |

Rud (2018) begins by telling us what he hopes to do in his chapter –

I will… try to develop an understanding of subjectivity which links person-centred therapy as a political practice that spills over onto the social field with a democratic political project that contains a similar philosophical basis of shared power, acceptance of differences, and the search for the common good that Spinoza (Negri, 2004; Deleuze, 2001) defines as multitude.

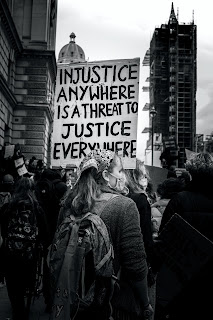

He then goes on to describe both “political considerations” and “politics and psychotherapy.” My first response to reading the chapter was frustration at a reaching back to Western philosophy again with the citing of Spinoza. Of course, I know nothing about Spinoza – and my first thought was, “Why not just cite bell hooks, and the critical race and queer feminists like Sara Ahmed!”

But after a while, I calmed down a bit, and reminded myself, that I can read all these folks, and that I don’t need to be intimidated. I can learn about Spinoza – he was a 17th century Portuguese Sephardic Jewish Dutch philosopher. That reminded me of reading the book, The Weight of Ink, by Rachel Kadish – that took me on a hunt to learn more about the Portuguese and Spanish Sephardic Jewish migration to Amsterdam and then to London post Inquisition!!

Anyway, the reality was that I really enjoyed Rud’s chapter, once I did a deep reading. I also particularly liked Rud’s discussion of Spinoza’s concept of the “multitude.”

But first, another description of neoliberalism – and its effects.

The kind of politics I am describing here promotes meritocracy, individualism (i.e. being a business person whose business is oneself) and the ‘selfie’ image. It presents itself as reality and truth, fracturing social bonds, insinuating itself among us in everyday life as a novel form of submission. With the emergence of a pacifying and democratic speech, we happily swallow the new drink Neo-Liber that transforms reality and ethics into ‘post-truth’ or ‘alternative reality’. The drink spills over onto our culture in the form of psychological suffering that requires in turn a ‘selfie’ psychotherapy that reproduces the logic of giver (therapist) and taker (client) and that finally reinstalls the formula of the possessor and the dispossessed.

The above formula adopts the semblance of benevolence, but as a matter of fact installs the supremacy of the ‘generous’ possessor who does not appreciate the value of what he receives. In the case of psychotherapy, the client often has the courage to entrust his or her pain, suffering and vulnerability, while often the therapist does not adequately value what has been given.

I’m moved by this warning of “benevolence” and the “generous possessor.” How many times do I think my job is to give my clients “tools” to manage their anxiety or emotional dysregulation? When I’m less full of myself, I remember to ask them, “what helps?” To remember that my clients are not “inferior” to me – they do not know less about how to live their own lives than I do! If anything, it can be my job to be curious with them about the ways they are coping – and the ways our imaginations and the arts can help them experience themselves differently.

I want to unpack this a bit – but this post is already too long… for now, I’ll just put the section that stood out!!

In Spinoza (1994), the notion of Multitude represents instead a plurality that persists as such, without ever converging into One or a unity, with a common expressive power that, nevertheless, respects the singular multiplicity. The Spinozist ‘multitude’ is democratic in a double sense: on one hand, as a designation of a popular power, an inalienable and non-transferable power, a right in act constitutive of the social reality; on the other hand, democratic multitude means preservation of the differences that constitute it by nature, resistance to uniformity; multiplicity without centre that never admits to be reduced to unity.

A multitude is a fabric of relationships, which allows us to think of the singular as an effect, as a knot of a moving weave of relationships, from which the notion of an individuality cut off from its surroundings is meaningless. Inspired by this process of intertwining between the human and the world, and from human to human, the building of community becomes the heart of the psychotherapeutic endeavour. In a sense, this means turning the practice of psychotherapy back to the world from which it emerges.

In accordance with the more general definition of multitude, I propose an understanding of the psychotherapeutic encounter as a micro multitude where the increase of common power does not imply the effacement of each singular power. When we affirm that we are but interwoven, expressive knots in constant movement and transformation, we also affirm that when we face another in the therapy room, we are being mutually constituted; there is an essential, reciprocal, inevitable mutuality in the encounter which I define as radical reciprocity. We are there, being other in front of another, mutually constituting one another in that moment. This effectively means displacing the ‘internal statistic’ from the viewpoint of the therapist who believes he or she knows whom he or she is going to meet. This applies to the other as well, and in this sense there is a mutual venturing out towards the encounter without intention to control, coming instead from the deep desire of meeting with another and with oneself.

Comments