Day 52 – Understanding the stories we tell ourselves and are told by others

|

| Photo by madison lavern on Unsplash |

As I think about it, I wonder if my problem is not so much managing the complexity of ideas, although, I know that is part of it. But rather, the intensity of emotions that these ideas generate – the fear, sadness, helplessness, grief, rage, guilt, and anxiety that arises as I confront sociopolitical and personal “realities.”

He reminded me of one of my own personal “lessons” for myself, and my students, when I first stated teaching. That was, to learn to tolerate intense affect! To understand arts’ capacity to hold intense affect, and to find ways that I, my students, and my clients could be in relation with intense feelings without the need for fight, flight, freeze, flop, or fawning. These terms are now used by neuroscience to understand the body’s response to “overwhelming or terrifying events” - see https://cotswoldcentrefortraumahealing.co.uk/how-ptsd-occurs/, but I think I underestimate the many ways this plays out. Even feeling overwhelmed by a theory or an idea I think I should know, can sometimes generate a form of this “dissociation” and a hijacking of my rational thinking mind to these instinctual somato-affective responses.

Harari (2018) ends his book by offering the practice of meditation as a means of understanding the self and the nature of suffering. There is also the possibility of learning more about how the sensations within our bodies are connected to the flow of our minds.

if you want to know the truth about the universe, about the meaning of life, and about your own identity, the best place to start is by observing suffering and exploring what it is. The answer isn’t a story. (pp. 258-259)

The technique of Vipassana is based on the insight that the flow of mind is closely interlinked with sensations of the body. Between me and the world there are always bodily sensations. (p. 262)

Harari notes that there are many ways of understanding and “dealing with the mysteries of the human mind.” He notes that, “it is easier to act and cooperate effectively when you understand the human mind, understand your own mind, and understand how to deal with your inner fears, biases, and complexes” (p. 263).

Meditation is far from being the only way to do all that. For some people, therapy, art, or sports can be more effective. When dealing with the mysteries of the human mind, we should regard meditation not as a panacea but as an additional valuable tool in the scientific tool kit. (p. 263).

For many folks, being left alone to observe and reveal the flow of their minds, and to attend to the sensations of their bodies as a means to encounter the source of suffering is quite difficult, or even not possible. Some folks need to be accompanied (is that our job as arts therapists?). For some of us that quest for understanding happens in therapy and art, and certainly change happens when we work together.

Harari says,

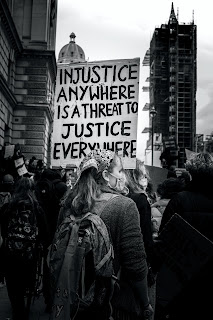

To change the world, you need to act, and even more important, you need to organize. Fifty members cooperating in an organization can accomplish far more than five hundred individuals each working in isolation. If you really care about something—join a relevant organization. Do it this week. (p. 263).

Harari, Y. N. (2018). 21 Lessons for the 21st Century. Random House Publishing Group. Kindle Edition.

Comments