Day 27 – Disability justice, arts activism, and Sins Invalid

Day 27 - I sort of wish I was a more disciplined researcher – I often stumble upon, expose myself to multiple sources of information, and follow up without noting the original sources of my interests or finds… so it is, with the book, Care work: Dreaming disability justice by Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha (2018). I bought the book several years ago but cannot remember now why or where I heard of it. Also, the book Feminist Queer Crip by Alison Kafer (2013), bought in May of 2018 along with Queer: A graphic history by Meg-John Barker and Jules Scheele. How did I come to these voices? And how is it that I’m only now delving into it a bit more??

Also, again – can’t even tell you why, but a few weeks ago I insisted on going to the Porter Square bookstore to buy Crip kinship: The disability justice & art activism of Sins Invalid by Shayda Kafai (2021). Couldn’t tell you why I needed to go immediately to buy the book, except that I knew that their mission was something I needed to know more about and that their work was definitely kin to my ideas about expressive arts therapy and social justice.

In Kafai’s (2021) chapter on “Artmaking as Evidence” – she writes,

Since their birthing, Sins Invalid engages with multidisciplinary artmaking to embolden and sustain crip-centric liberated zones. Art made by disabled, queer of color community becomes sustenance and strategy for crip-centric resilience. Similar to storytelling, artmaking gives us a voice and a language with which to love our bodyminds in the face of intersecting oppressions. This type of politicized artmaking moves disability past shame and towards pride and liberation. Here, liberation becomes modern dance choreographed by Deaf dancers. Liberation becomes a crip striptease performed on a wheelchair. It becomes an unlearning of a past of emotional abuses through poetry. Liberation becomes challenge, transformation, and potential. (p. 87)

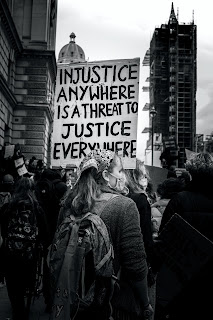

This writing reminds me that the healing, liberatory, transformative power of the arts is not owned by the arts therapies – they have always existed and continue to exist. I must beware of posing an articulation of expressive arts therapy that takes advantage of the history of arts activism in disability justice work without crediting those whose work and words were so hard won. Piepzna-Samarasinha (2018) cautions against this erasure and watering-down when she writes,

I’d like to offer a quick definition and history of what we mean when we say the words “disability justice.” This is important for so many reasons but especially because our work terminology are in danger, now and always, of having the fact that they were invented by Black, Indigenous, and people of color erased and their politics watered down. There is a specific danger in that happening with disability justice, as disabled Black and brown creators face a specific invisibilization and erasure of our political and cultural work. (p. 20).

So, I suggest you go to the Sins Invalid website and download a copy of the Disability Justice primer, and I offer the words of Patty Berne, as cited by Piepzna-Samarasinha (2018),

While a concrete and radical move forward toward justice for disabled people, the Disability Rights Movement simultaneously invisibilized the lives of peoples who lived at intersecting junctures of oppression—disabled people of color, immigrants with disabilities, queers with disabilities, trans and gender non-conforming people with disabilities, people with disabilities who are houseless, people with disabilities who are incarcerated, people with disabilities who have had their ancestral lands stolen, amongst others … Disability Justice activists, organizers, and cultural workers understand that able-bodied supremacy has been formed in relation to other systems of domination and exploitation. The histories of white supremacy and ableism are inextricably entwined, both forged in the crucible of colonial conquest and capitalist domination. One cannot look at the history of US slavery, the stealing of indigenous lands, and US imperialism without seeing the way that white supremacy leverages ableism to create a subjugated ‘other’ that is deemed less worthy/abled/smart/capable … We cannot comprehend ableism without grasping its interrelations with heteropatriarchy, white supremacy, colonialism and capitalism. Each system benefits from extracting profits and status from the subjugated ‘other.’ 500+ years of violence against black and brown communities includes 500+ years of bodies and minds deemed ‘dangerous’ by being non-normative.

A Disability Justice framework understands that all bodies are unique and essential, that all bodies have strengths and needs that must be met. We know that we are powerful not despite the complexities of our bodies, but because of them … Disability Justice holds a vision born out of collective struggle, drawing upon the legacies of cultural and spiritual resistance within a thousand underground paths, igniting small persistent fires of rebellion in everyday life. Disabled people of the global majority—black and brown people—share common ground confronting and subverting colonial powers in our struggle for life and justice. There has always been resistance to all forms of oppression, as we know through our bones that there have simultaneously been disabled people visioning a world where we flourish, that values and celebrates us in all our myriad beauty. (Berne, as cited in Piepzna-Samarasinha [2018], p. 20-21)

Berne, P. (2017, May). Skin, tooth, and bone—the basis of our movement is people: A disability justice primer. Reproductive Health Matters 25, 50, 149–50.

Kafai, S. (2021). Crip kinship: The disability justice & art activism of Sins Invalid. Arsenal Pulp Press.

Piepzna-Samarasinha, L. L. (2018). Care work: Dreaming disability justice. Arsenal Pulp Press. Kindle Edition.

Comments