Day 9 – What does it mean for us to say we have our “roots” in Indigenous practice?

|

| Photo by Nicole Geri on Unsplash |

In 1999, the first text to “gather a multiplicity of perspectives which represent the field of expressive arts therapy” was edited by Stephen and Ellen Levine (p. 9). They trace the early training of arts therapists in an “interdisciplinary approach” introduced at Lesley College in the early 1970s. Lesley’s program was noted to be in “contradistinction to the specialized arts therapy training programs then in existence” (p. 9). The original faculty at Lesley were trying to promote a new, integrated arts approach to “therapy,” where total expression was elevated.

In the forward to Knill, Barba & Fuchs’ (1995) germinal work, Minstrels of soul: Intermodal expressive therapy, McNiff writes, “We instinctively knew that the vitality of imagination was furthered through the engagement of all expressive faculties. Since opportunities for this type of study did not exist at any other school, we felt ourselves charged with a mission” (p. 10).

Yet, from the beginning, “connections were made with indigenous healing systems, such as shamanism (McNiff, 1981), and with contemporary philosophical developments, such as phenomenology, hermeneutics, and more recently, deconstructionism” (Levine & Levine, 1999, p. 9). Knill, Barba, and Fuchs (1995) equate their work to “soul work” – and draw on the “anthropological roots” of arts, play, and imagination in “human rituals” as a foundation for understanding “the interdisciplinary tradition in the practice of the arts” (p. 22-23). They continue, “Art in its purest form is primarily a ritual activity that is practiced in an elaborate manner only by humans and has no evident ‘goal’ other than celebrating creativity and human potential” (p. 23).

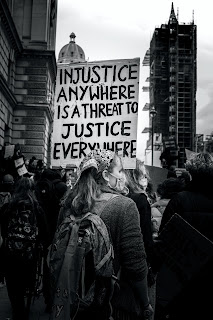

This statement seems to emerge out of the same “universalism” Napoli (2019) describes, and the same “racially-evasive and depoliticized” orientation described by Norris (2020).

Napoli (2019) does important work in describing how these ideas, without a “relationship with the Native informants of knowledge” and with a reconceptualization of “Native collective knowledge as universal knowledge is a form of cultural appropriation” (p. 4). She writes,

Although the positioning of art therapists as “twentieth century shamans” was a function of the times, coming out of widespread dominant cultural practices of cultural appropriation during the mid-20th century, multiple generations of art therapists have been educated using these concepts without deconstructing this positioning of Indigenous healers as frozen in the past, universal archetypes, or as a metaphor.

How do we begin to tease out an articulation of the theory and practice of expressive arts therapy from this legacy of colonial amnesia, situated and subjugated knowledge, and cultural appropriation?

Napoli, M. (2019). Ethical contemporary art therapy: Honoring an American Indian perspective. Art Therapy: Journal of the American Art Therapy Association, 36(4), 175–182.

Comments